2. Executive Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered one of the most volatile economic recessions the United States has seen. Millions of Americans most proximately felt the impacts of increased inflation, higher food insecurity, and pricier bills for rent, groceries, emergencies, and other critical expenses. The “Great Resignation” trend of voluntary unemployment due to untenable costs of living and stagnant wage adjustment to Pandemic-era circumstances magnified a larger societal problem that has been deep-rooted in the American labor system for decades: low minimum wages. A rapidly changing American economy has necessitated greater attention & action toward pressing problems faced by millions of workers across minimum wage jobs: a lower standard of living.

The fragmented nature of different minimum wages as well as adjustment methods across U.S. states, territories, and federal districts, paired with a general lack of federal minimum wage adjustment due to political inertia and resistance, has become an existential threat to minimum wage workers who are unable to self-determine and control the trajectory of their life. Minimum wages that do not track higher costs to live is one of a myriad of labor/social issues workers face on a daily basis.

Simply put, this brief evaluates the state of minimum wages on both the domestic and international level, examining its associated impacts and sentiment on a societal dimension.

To achieve this, we analyze the relevant stakeholders, such as governments, companies, communities, and so on to determine the viability of federal minimum wage increases in the United States. We attempt to harmonize the disunited incentives of these different stakeholders to produce the best possible outcome for all parties.

This brief stands in favor of increasing the minimum wage, examining the issue through a discursive approach (with internal refutation to common claims against raising the minimum wage). We suggest comprehensive policy action to catalyze minimum wage increases across the United States and synthesize current inflation indices to re-examine and act upon the ongoing labor crisis.

3. Background

3.1 What is Minimum Wage?

Minimum wage is the lowest (minimum) payment/compensation employers must provide for their employees for the work they complete on an hourly basis, serving the purpose of creating a “lowest common denominator” standard of living while mitigating exploitation and effects of economic inequality. Workers in different segments of the market vary in skill level depending on the occupation, so the absence of a minimum wage would disadvantage those who work unskilled or low-skill jobs (where lower wages & exploitation could be justified on the basis of their work). Minimum wage rates are set by municipal, state, and federal governments, with the higher wage rate applying to the workplace.

In the United States, a minimum wage was first established in response to the Great Depression through Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal-era National Industry Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, which established a host of regulatory policies and frameworks such as minimum rates of pay, maximum work hours, working condition stipulations, and collective bargaining agreements/union formation protections. In Schechter Poultry v. United States (1935), NIRA was struck down unanimously by the Hughes Court based on an “unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority” to the executive for the purpose of regulating industries without Congressional guidelines for implementing the policy.1 The Court additionally held that the company’s activities did not fall under the purview of interstate commerce, the only type of commerce Congress was permitted to directly regulate. Schechter implicitly established the precedent that the creation of labor policy must be concentrated within legislative action, though higher-level court cases dictating constitutionality had a hand in shaping laws (as proven in cases such as National League of Cities v. Usery2, Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority3, and so on). Just three years later, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) was passed by the 75th U.S. Congress, which instituted a federal minimum wage, overtime pay, and a ban on child labor. Adjustments to the federal minimum wage with the FLSA have been made since 1938. A series of amendments to the FLSA throughout history. starting in 1940 creating special industry committees to set minimum wages on an industry-by-industry basis in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, provided crucial clarification and adjustments to minimum wages for different industries. The current U.S. federal minimum wage, as set in July 2009, stands at $7.25 an hour.

Fig. 1: FLSA Amendments via Legislative/Judicial Action*

| Amendment Title & Date of Passage | Notable Effect of Amd. (not exhaustive) |

| 1940 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – June 26, 1940 | Established Special Industry Committees (SICs) to set minimum wages in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands territories on an industry-by-industry basis. |

| Portal-to-Portal Act – May 14, 1947 | Delineated the difference between workday activities that mandate compensation (i.e. work breaks, fire drills, etc.) versus those that do not (i.e. vacation & sick days for unsalaried workers) |

| 1949 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – October 26, 1949 | Increased the minimum wage from $0.40/hr to $0.75/hr, expanded the new $0.75/hr minimum wage to workers in the aircraft & seafood industries, and eradicated SICs in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands territories. |

| 1955 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – August 12, 1955 | Increased the minimum wage from $0.75/hr to $1.00/hr to all pre-existing industries as stipulated in the 1949 Amendment. |

| 1961 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – May 5, 1961 | Mandated the incremental increase of the minimum wage from $1.00/hr in September 1961 to $1.25/hr in September 1963 for previously covered workers. |

| 1966 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – September 21, 1966 | Extended minimum wage coverage to hospital, public school, farm, construction, and state/national-level government workers. |

| 1974 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – April 8, 1974 | Mandated the incremental increase of the minimum wage to $2.30/hr in 1976 for non-farm workers. |

| 1977 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – November 1, 1977 | Reached $2.30/hr for farm workers (parity with non-farm workers) and incrementally increased the minimum wage from $2.65/hr in January 1978 to $3.35 in January 1981. |

| 1985 Supreme Court Case Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority et. al. – February 19, 1985 | Overturned the outcome of National League of Cities v. Usery (1971) and held that SAMTA, a governmental function, needs to follow FLSA/minimum wage/overtime pay policies. |

| 1985 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – November 13, 1985 | Mandated FLSA application to public sector employees with state/local-level government officials to be compensated 1.5x for each hour of overtime worked. |

| 1986 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – October 16, 1986 | Created Section 14(c) of the FLSA, permitting employers paying a subminimum wage to employees whose disabilities affect work productivity. |

| 1989 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – November 17, 1989 | Mandated the incremental increase of the minimum wage from $3.80/hr in April 1990 to $4.25/hr in April 1991. |

| 1996 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – July 10, 1996 | Mandated the incremental increase of the minimum wage to $5.15/hr in July 1997. |

| 2007 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act – May 25, 2007 | Mandated the incremental increase of the minimum wage from $5.85/hr in July 2007 to $7.25/hr in July 2009. |

Data sourced from the U.S. Dept. of Labor4

The above table summarizes the major impacts of direct FLSA amendments over the years. Most amendments occur for the purpose of incremental increases to wages, but earlier wages were split between different sectors (i.e. interstate commerce/production of interstate commerce goods and services [1938 Act], retail & service enterprises [1961 Amendments], non-farm [1966 and subsequent Amendments], and farm workers [1966 and subsequent Amendments]).

Across all federal minimum wage adjustments with amendments, most occur with incremental increases.

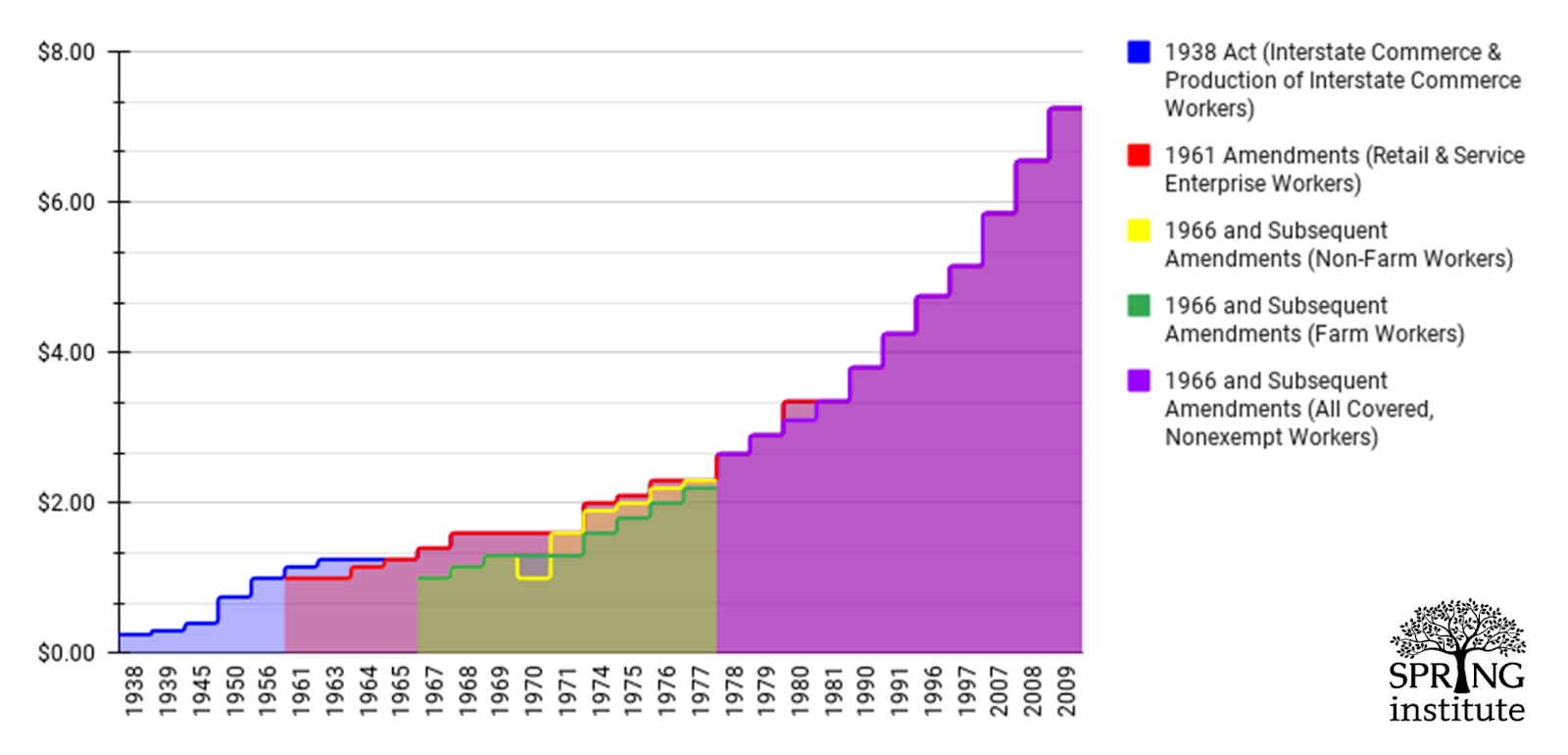

Fig. 2: Historical Gradations in the Federal Minimum Wage

Data aggregated from the U.S. Dept. of Labor5

Data visualization of non-inflation adjusted minimum wage increases are shown above in Figure 2. Note that the 1938 Act (interstate commerce & production of interstate commerce goods and services) and 1961 Amendments (retail & service enterprise workers) achieve convergence/parity in rates by 1965, which explains the overlap of lines at that point in time. The 1961 Amendments (retail & service enterprise workers) and 1966 & Subsequent Amendments (all FLSA-covered, nonexempt workers) achieved convergence in rates by 1981, which explains the overlap in lines at that point in time. The bifurcation of minimum wage rates by farm and non-farm workers commenced in 1967 and ceased in 1977.

3.2 Minimum Wage & Pay Standards Globally

Minimum wages are set differently in accordance to each country’s respective policy for pay adjustment. The Pew Research Center quantifies that wages set by statute, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act in the United States, join 16 other minimum wage-providing countries. Statutory-based adjustments to minimum wage entails the direct amendment of pre-existing policy by lawmakers. In contrast, at least 115 countries pass new minimum wage rates by virtue of regulation through decrees and orders. Roughly three-quarters of those regulatory-based countries facilitate governmental action “after input from workers’ and employers’ organizations”.6 145 countries concentrate and retain minimum wage authority within the central government. Comparatively, local and state governments retain concurrent powers to set their own minimum wages in the United States and only six other countries (India, China, Indonesia, Canada, Australia, Iran, and Bosnia & Herzegovina) delegate minimum wage adjustment power to subnational units of government. Such instances of devolution in regards to minimum wage-setting has its clear benefits and harms; on one hand, it provides lower-level governments more flexibility in accordance to each locale’s needs, but on the other, it creates an inconsistent wage standard

For countries that aim to rectify the latter concern, 43% of countries with minimum wage systems opt for an overarching national minimum wage whereas others set rates based on different sectors/industries through collective bargaining agreements with unions (such as Austria).

At least 80 countries mandate the reassessment and review of minimum wages every year or every two years- the United States is not on that list.

3.3 Minimum Wage & Pay Standard in the United States

Minimum wage in the United States is set by multiple tiers of government: local, state, and national (with the larger governmental body superseding the minimum wage for businesses if the lower-level government’s rate is less than that of the larger government’s minimum wage stipulation). For instance, Wyoming and Georgia’s state-level minimum wage of $5.15, though not directly overwritten, is subsumed by the federal minimum wage of $7.25 (the state minimum wages only apply for non-FLSA covered businesses & FLSA-exempt employees). The same precedent applies in reverse, where a larger minimum wage set by a lower tier of government will overtake a lower minimum wage set by a higher governmental body.

Minimum wages have become an all too familiar part of the American labor experience, with 247,000 workers making $7.25 an hour (amounting to less than $15,000 a year working 40-hour workweeks). Zippia quantifies that 44.3% of workers making minimum or subminimum wages are under the age of 25. Crucially, of the American workforce, over a third (~52M Americans) receive less than $15 an hour.7

A notable section of the federal definition of minimum wage (per the 2007 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act) is as stipulated in 29 U.S. Code Chapter 8 § 206:8

“Every employer shall pay to each of his employees who in any workweek is engaged in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce, or is employed in an enterprise engaged in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce, wages at the following rates:

- except as otherwise provided in this section, not less than—

- $5.85 an hour, beginning on the 60th day after May 25, 2007;

- $6.55 an hour, beginning 12 months after that 60th day; and

- $7.25 an hour, beginning 24 months after that 60th day;”

3.4 Methods of Minimum Wage Adjustment

Each local and state method for setting and adjusting minimum wage rates differ. A March 2023 Congressional Research Service report identifies two primary methods:9

- “legislatively scheduled rate increases that may include one or several increments”

- “a measure of inflation to index the value of the minimum wage to the general change in prices.”

Method 1: Incremental Increases Through Legislature

Most federal minimum wage adjustments made to the Fair Labor Standards Act have used this system. Legislation is drafted, sponsored/cosponsored, processed through relevant committees (amended as necessary), and sent to the House and then Senate for voting following committee approval. On the national level, statutory-type adjustment notably is more difficult to enact change in, given the political resistance & barriers that need to be surmounted.

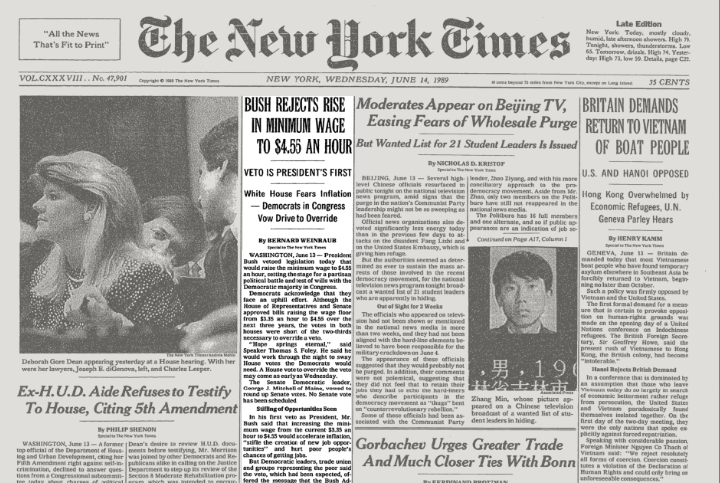

Case Study: 1989 Amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act10

In 1989, a newly-elected President George H.W. Bush campaigned on the promise to increase the minimum wage (a policy position that was widely supported by both the House & Senate), but promised to veto any minimum wage exceeding $4.25/hr. Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA), confident in overturning a veto with strong Congressional backing, pushed for a $4.55/hr minimum wage FLSA Amendment proposal (which passed the House 248-171 and Senate 61-39). Bush vetoed the amendment and Congress failed to overturn the veto. A new Amendment with a $4.25/hr proposal was soon introduced and approved by committee, passed through the House and Senate, and signed by President Bush.

The June 14, 1989 edition of The New York Times cover page.

Paper sourced from The New York Times Archive.11

Expanded discourse on the merits and demerits of minimum wage adjustment by virtue of legislators (as opposed to economic technocrats) will be further analyzed in Section 4.1 of this brief.

Method 2: Increases Pegged to Inflation Indices

As of September 6, 2022, 13 U.S. states/federal districts (Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, South Dakota, and Vermont, Washington, and Washington D.C.) adjust the minimum wage in accordance to the cost of living with an inflation index.12 States that have passed index-based minimum wage increases that have not yet seen effects include California, Connecticut, Florida, Oregon, and Missouri.13

Most states included in the above list opt to use the Consumer Price Index, which functions as “a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.” The Consumer Price Index mechanistically weights the twelve-month averages of price fluctuations on various item categories such as housing, transportation, medical care, food & beverages, and more.14

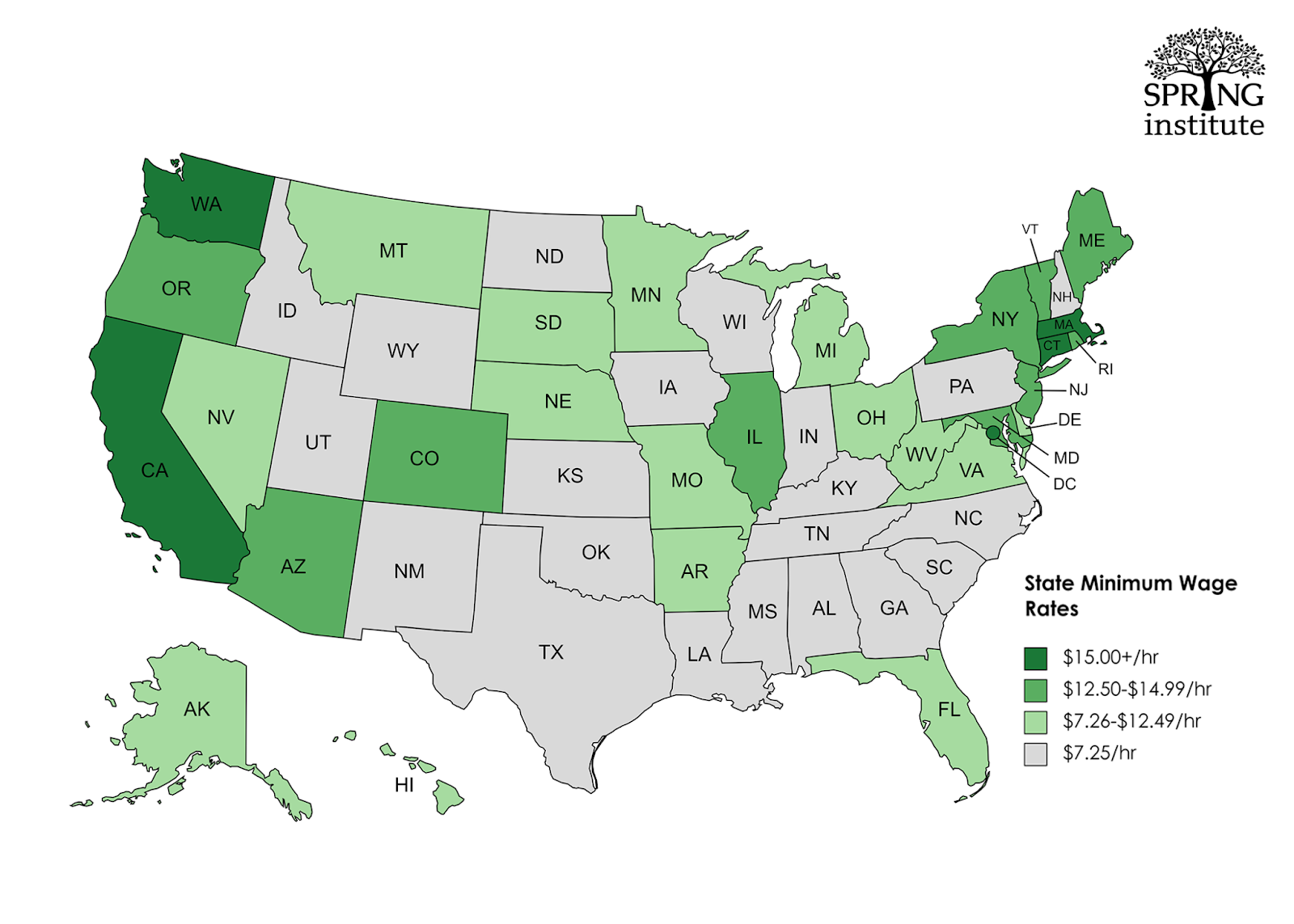

Fig. 3a: Minimum Wage Rates by State (excl. Territories)

Fig. 3b: Minimum Wages for FLSA-Covered Businesses (incl. Territories)†

| AL* - $7.25 | AK - $10.85 | AS** - Special | AZ - $13.85 | AR - $11.00 |

| CA - $15.50 | CO - $13.65 | CT - $15.00 | DE - $11.75 | FL - $11.00 |

| GA*** - $7.25 | GU - $9.25 | HI - $12.00 | ID - $7.25 | IL - $13.00 |

| IN - $7.25 | IA - $7.25 | KS - $7.25 | KY - $7.25 | LA* - $7.25 |

| ME - $13.80 | MD**** - $13.25 | MA - $15.00 | MI - $10.10 | MN***** - $10.59 |

| MS* - $7.25 | MO - $12.00 | MT****** - $9.95 | NE - $10.50 | NV******* - $11.25 |

| NH - $7.25 | NJ - $14.13 | NM - $7.25 | NY******** - $14.00 | NC - $7.25 |

| ND - $7.25 | MP - $7.25 | OH********* - $10.10 | OK - $7.25 | OR********** - $14.20 |

| PA - $7.25 | PR - $9.50 | RI - $13.00 | SC* - $7.25 | SD - $10.80 |

| TN* - $7.25 | TX - $7.25 | UT - $7.25 | VT - $13.18 | VA - $12.00 |

| VI - $10.50 | WA - $15.74 | WV - $8.75 | WI - $7.25 | WY*** - $7.25 |

| DC - $17.00 |

Figures 3a & 3b data sourced from the U.S. Dept. of Labor.15All wage rates depicted are as of the date of publishing of this brief.

Footnotes

†Table excludes local/municipal-specific minimum wages- it only includes territorial-, state-, federal district-, and national-level minimum wages (and the one displayed in each box is the highest of all governmental tiers accounted for).*The states of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee have no state minimum wage law; therefore, they default to FLSA federal minimum wage.

**American Samoa has minimum wage rates based on industry.

***The states of Georgia & Wyoming have minimum wages at $5.15 for non-FLSA covered businesses and $7.25 per FLSA federal minimum wage for FLSA-covered businesses.

****Maryland has two minimum wages- $12.80 for businesses with <15 employees, $13.25 for business >15 employees.

*****Minnesota has two minimum wages- $8.63 for businesses with <$500K annual revenue, $10.59 for businesses >$500K annual revenue.

******Montana has two minimum wages- $4.00 for non-FLSA covered businesses with <$110K in annual sales, $9.95 for businesses with >$110K in annual sales

*******Nevada has two minimum wages- $11.25 for healthcare insurance non-qualifying/uncovered employees, $10.25 for healthcare insurance qualifying/covered employees

********New York City, Westchester, and Long Island have minimum wages of $15.00; the rest of New York is set at $14.00.

*********Ohio has two minimum wages- $7.25 for businesses with annual gross receipts <$372K, $10.10 for businesses with annual gross receipts >$372K

**********The Portland Metro Area has a minimum wage of $15.00, non-urban counties have a minimum wage of $13.20; the standard state rate is set at $14.20.

3.5 Domestic Sentiment

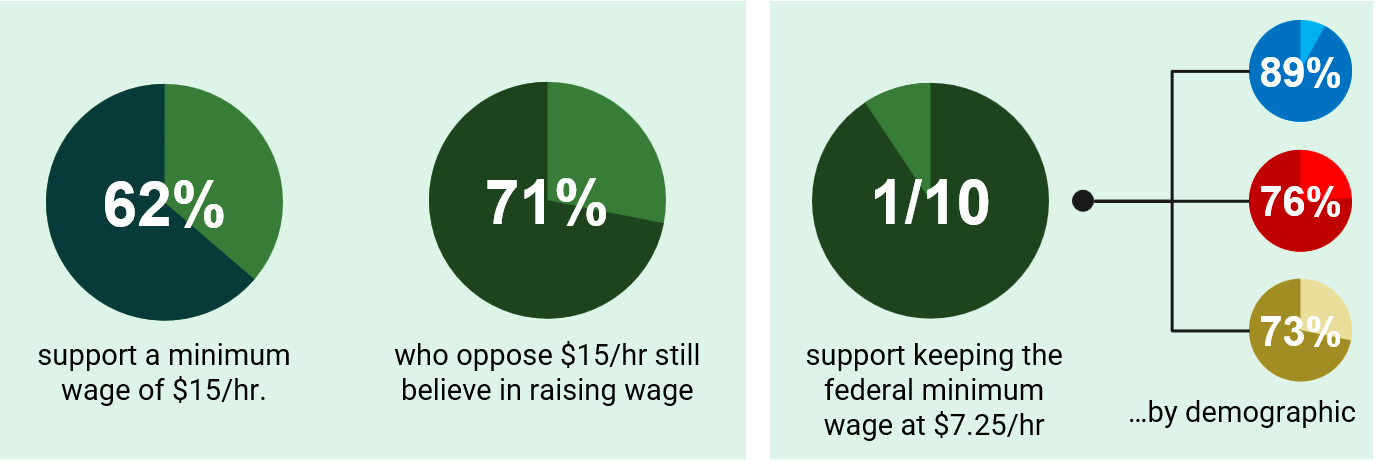

There exists strong support for higher minimum wages across the board. Fig. 4 quantifies public support for raising the wage.

Fig. 4: Public Support of Minimum Wage Increases

Data sourced from the Pew Research Center

The support for minimum wage increases have ramped up over the years, with major minimum wage protests (i.e. the “Fight for $15” movement in 2012) coinciding with other labor-related issues (such as unionization). The persistence of inflation brought to the fore a labor force discontent with the state of pay and quality of life.

4. Stakeholder Analysis

4.1 Employees

Minimum wage laws have been established with the intention of safeguarding the well-being of low-income workers and addressing the pressing issue of income inequality. The presence of a minimum wage contributes to a baseline standard of compensation for employees, aiming to ensure that their earnings align with a certain level of dignity and fairness.

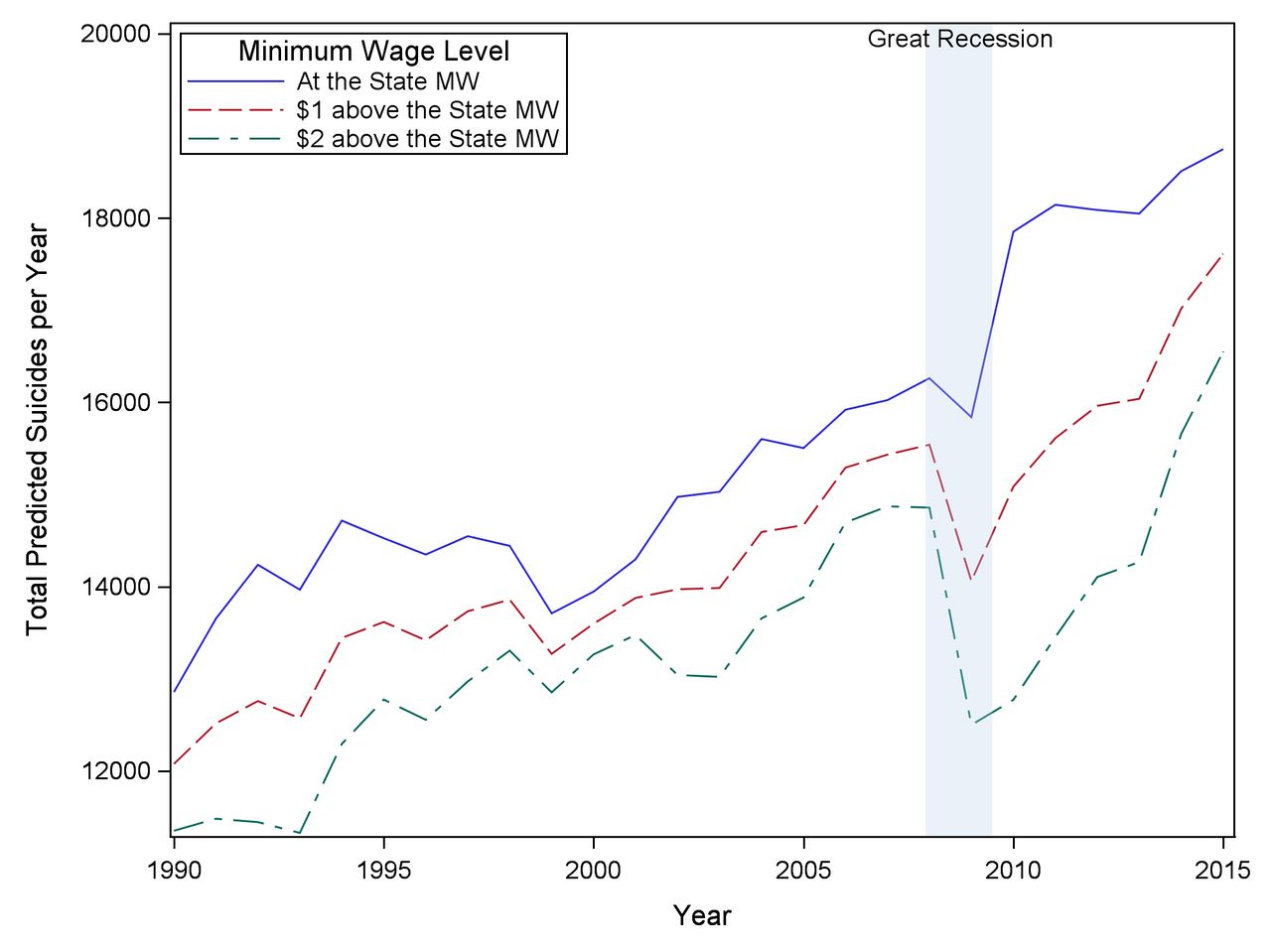

The assurance of a minimum wage provides a degree of financial stability and predictability that can alleviate stress and anxiety for workers. Knowing that their earnings will not fall below a certain threshold provides a sense of security and reduces concerns about basic needs such as housing, food, and healthcare. As shown in Fig 5 below, a higher minimum wage is often correlated with lower risks of suicide due to the level of financial security it provides.

Furthermore, the German Institute for Economic Research states that a minimum wage leads to “a significant increase in well-being with respect to life, job, and pay satisfaction.” 16 When employees feel that their efforts are being adequately compensated, they are more likely to experience higher levels of job satisfaction. This, in turn, positively influences their mental health by promoting a sense of accomplishment and pride in their work.

The benefits of minimum wage on employees transcends its economic underpinnings, extending into the mitigation of potential exploitation. A minimum wage acts as a counterbalance to the potential power differentials that can exist between employers and employees. The absence of such a safeguard can create an environment wherein employers possess a disproportionate share of power, exerting it to their advantage while potentially subjugating employees to suboptimal working conditions and inequitable compensation. The psychological toll of such exploitation manifests in feelings of disempowerment, disillusionment, and even alienation.

Fig. 5: Effect of Minimum Wage on Suicide Rates

Data sourced from Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health17

4.2 Small-to-Midsize Enterprises

For small-to-midsize enterprises, they typically operate on more thin profit margins and have limited resources. Most of them have single-digit profit margins, extremely price-sensitive customers, and no room to absorb a substantial increase in the minimum wage without dramatically reducing the cost of service. In fact, about half the minimum-wage workforce is employed at businesses with fewer than 100 employees, and 40% are at very small businesses with fewer than 50 employees.18

The impact of a substantial increase in the minimum wage can lead to what is commonly referred to as the "Walmart effect," particularly affecting small and midsize businesses. This phenomenon is characterized by a scenario in which larger corporations with greater financial resources can absorb the cost of the wage increase more effectively, giving them a competitive edge over local businesses. As the minimum wage rises, workers may gravitate towards opportunities that offer higher wages, often favoring larger establishments. This dynamic poses a significant challenge for smaller businesses, which find it difficult to match the increased wages offered by larger competitors while maintaining their price competitiveness.

Such harm carries a twofold effect that encompasses both the labor market and the broader economic landscape. First, employees of small businesses may lose their jobs due to a strain on the corporation’s budget. Secondly, the harm experienced by small businesses can exacerbate monopolization and concentration of economic power in the hands of a few large corporations. When small businesses close due to competitive pressures from larger entities, the result is a shrinking marketplace with fewer options for consumers. This reduction in competition can stifle innovation, limit consumer choice, and drive up prices.

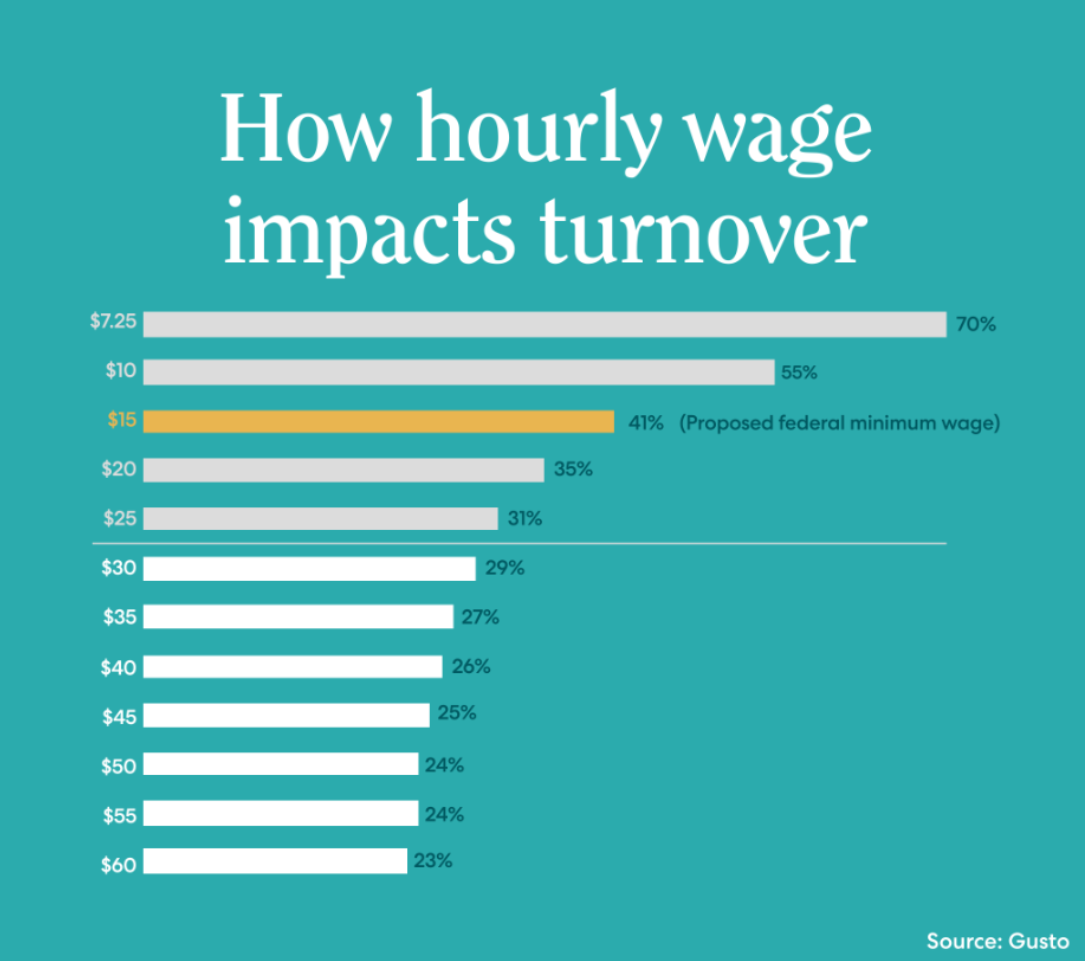

4.3 Large Businesses & Corporations

For many large businesses, the adoption of increased wage thresholds leads to a notable improvement in employee retention rates, a critical concern for major corporate entities. As evidenced by Fig. 6, workers who are paid the present federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour face a 70% probability of departing their positions within a year.19 However, when the hourly wage is increased to $15, the turnover rates show a notable decrease from 70% (the existing federal minimum wage) to 41%.This reduction in turnover carries financial benefits by decreasing recruitment and training costs and fostering a more experienced workforce. This dynamic is exemplified by Walmart's shift towards higher wages, which contributed to improved staff retention and highlighted the connection between equitable compensation and employee commitment.

Fig. 5: Effect of Minimum Wage on Employee Turnover

Data sourced from Gusto, CNBC20

In the context of minimum wage harms toward businesses, larger corporations are generally less impacted than their smaller counterparts. This discrepancy can be attributed to several specific reasons:

- Access to Capital: Starbucks, as a larger corporation, has access to multiple sources of capital that enable it to adapt to wage changes. It can secure funds for strategic adjustments, such as redesigning store layouts or implementing digital ordering systems. On the other hand, a local coffee shop might struggle to secure the necessary funding for similar adaptations.

- Economies of Scale: Larger corporations, such as Walmart, can navigate minimum wage hikes more effectively due to their extensive reach and revenue base. For instance, when minimum wages were raised in various locations, Walmart's ability to spread the increased labor costs across its vast network allowed it to absorb the impact without compromising its profitability.21 Smaller businesses, however, lack the same level of revenue cushioning.

- Resource Allocation: Companies like Amazon, with their ample resources, can invest in technology and process optimization to mitigate the impact of higher wages. Amazon's implementation of advanced automation technologies in its warehouses exemplifies how larger corporations can offset increased labor costs through innovative operational adjustments.22 In contrast, a smaller e-commerce business might lack the resources to invest in such technologies.

4.4 Government

Economic Effects on Government Revenues and Expenditures

As minimum wages rise, the incomes of low-wage workers naturally increase as well, potentially pushing some individuals into higher income tax brackets. This shift results in an augmentation of income tax revenue for the government's coffers. However, this effect can be tempered by the nuances of progressive tax systems, where higher-earning individuals are subjected to proportionately higher tax rates.

Role of Central Bank

Central banks play a pivotal role in managing the intricate interplay between minimum wage policies and inflation, employing a variety of strategies to ensure economic stability:

- First, the Central Bank may adjust interest rates. By raising interest rates, central banks can influence borrowing and spending behavior. This can help mitigate the potential inflationary pressures stemming from increased consumer spending due to higher minimum wages. The higher interest rates serve as a deterrent to excessive borrowing and spending, thus aiding in containing inflation.

- Second, the bank could intervene in market operations. Central banks can engage in the buying and selling of government securities to regulate the money supply within the economy. Selling government securities reduces the availability of money in circulation, which in turn curtails spending and can help curb inflationary tendencies resulting from increased demand associated with higher wages.

- Third, the bank could impose credit controls. When minimum wages increase, businesses and individuals might seek to borrow more to cover higher labor costs or increased consumer spending. While increased borrowing can stimulate economic activity, excessive credit growth can lead to financial imbalances and instability. Credit controls offer central banks a way to moderate the pace of borrowing and lending, thereby mitigating the potential negative consequences associated with sudden increases in credit demand resulting from minimum wage changes.

Social Spending

When minimum wage levels are increased, low-wage workers often experience a rise in their earnings. This enhanced income can lead to reduced reliance on government welfare programs, such as food stamps, housing assistance, and unemployment benefits. As individuals earn higher wages, they may surpass the income thresholds that qualify them for certain social assistance programs.

During the 1990s, the United States experienced a period of economic growth and saw several states raise their minimum wage levels. A notable example is the state of New Jersey, which increased its minimum wage in 1992.23 Research conducted by economists David Card and Alan Krueger found that the increase in the minimum wage led to an improvement in the earnings of low-wage workers without causing significant job loss, contrary to conventional economic theories at the time.

As a result of these higher earnings, some workers were able to move above the poverty line, reducing their reliance on government welfare programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid. This trend was observed across various states that raised their minimum wages during the same period.

5. Benefits of Minimum Wage Increase

5.1 Summary of Benefits

The American economy’s capacity to produce goods for consumers and financially accommodate workers has grown over the years. But as prices increase due to inflation and other factors, the minimum wage has struggled to keep pace. It seems that most goods are more expensive, but paychecks are not larger. For example, the cost of college is rising almost eight times faster than wages.24 This makes escaping cyclical poverty very difficult for most Americans as each paycheck is solely dedicated to paying the bills and surviving that month rather than building wealth. The scope of the issue is quite large as well. In fact, 42% of all employees in the United States make below $15 an hour and thus would get a pay raise if the minimum wage were to be raised to the $15 threshold. Granted, some of these workers are not the primary breadwinner for their households and are often teenagers working a job for extra spending money, but still, a fairly significant portion of these workers are low income considering that someone without a college degree does not have many higher-paying options. The problem lies in the fact that Americans can work extensive hours and still be unable to meet what is necessary to get by in modern-day America, as one in nine employees work full time but are still in poverty.25

This lack of pay and higher rates of poverty has devastating impacts on the working class. As of 2021, a $7.25-an-hour job cannot afford a two-bedroom rental apartment anywhere in the country.26 It doesn’t matter what state or county someone lives in, $7.25 can still not afford necessities. Raising the minimum wage would pay workers more, and thus limit the impacts of poverty. This is critical and is a mandatory component of policy making considering 4.5% of all deaths in the US, or about 150,000 deaths annually, are attributed to being in poverty.27 Moreover, from 2008 to 2012, a $15 minimum wage could have prevented 5,500 premature deaths in New York City alone.28

5.2 Improved Mental Health

Over the last several decades, economists have devoted considerable effort to studying the effects of minimum wage increases on the level of employment. More recently, economists have examined the effects of minimum wage increases on other social and economic outcomes, most notably, the mental health benefits on workers. The statistical association between poverty and worse health outcomes is well-known, including self-reported health, access to healthcare, and mental ill health. Through several different experiments there have been results pointing to a significant correlation between an increase in the minimum wage and low-wage worker’s mental health. The extent of this can be seen from effects on a person with an increase in minimum wage.

The first effect involves affordability. Higher wages allow workers to afford better goods and services, including higher quality food and water, cleaner and safer neighborhoods, gym memberships, and health care.

Second, studies document psychosocial or stress-induced effects on health, especially at the workplace. At least three streams of psychosocial pathways can be identified involving wages. The first involves job satisfaction. Economists present evidence that low wages negatively affect job satisfaction; epidemiologists provide evidence that low job satisfaction predicts poor physiological and psychological health. The second stream involves lack of social status. Humans are a social species, we value the respect of others which is partially determined by wages because they convey information about our position in the socioeconomic hierarchy. The final stream pertains to feelings of “control over destiny” which are elevated with rising incomes.

(https://www.zbw.eu/econis-archiv/bitstream/11159/368412/1/EBP075847531_0.pdf)

5.3 Workforce Productivity

Minimum wages laws prove to serve as work incentives. When the pay goes up, motivation does as well. Studies observed by Kellogg Business School show that employees work harder on average due to indicated increases in sales. Across all workers, sales went up by 4.5 percent in the observed company.29 This was especially seen with “low-performance” workers, who saw productivity spikes by 22.6 percent, and employee confidence was further proven by turnover levels where there were 19 percent lower terminations throughout that “lower-performance” group.30

These studies of positive increases in workforce productivity following increases to the minimum wage were furthered by The University of Chicago. Not only were the trends still found in low-performance workers who often relied on the minimum wage, the fear of losing a higher paying job forced many to increase their productivity out of the spur of motivation.31 In turn, termination rates went down like in the Kellogg statistics, for workers’ renewed efforts provided a reason to keep them employed.32 Overall, each Chicago study proved the same effect of new minimum wage laws where workforce productivity increases causing a more stable workplace environment all together.

5.4 Reduction in Exploitative Practices

Minimum wage laws serve as a deterrent against exploitative labor practices, acting as a safeguard that ensures fair compensation for workers. By establishing a clear baseline for wages, these laws significantly reduce the likelihood of unpaid labor practices, such as unpaid internships or forcing employees to work off the clock. Employers are acutely aware that failing to meet the minimum wage requirements can lead to legal repercussions and damage to their reputation.

Moreover, these laws mitigate wage theft, providing workers with a legal framework to identify and report instances where they are not paid the minimum wage or are underpaid. In the ten most populous U.S. states, around 2.4 million workers, spanning various demographic categories, suffer from minimum wage violations.33 This leads to a collective annual loss of $8 billion, averaging about $3,300 per year for those who work year-round.34 This loss represents nearly a quarter of their total earnings and affects 17% of low-wage workers.35 This increased clarity empowers employees to assert their rights and seek justice in an inherently unjust workforce.

The protection of a minimum wage becomes especially critical for marginalized workers, including young workers, women, people of color, and immigrant workers, who tend to report being paid less than the minimum wage more frequently. This discrepancy is largely attributed to the fact that they are also overrepresented in low-wage jobs. While the average annual sum withheld from individuals, both men and women, experiencing minimum wage violations stands at around $64 and $63 per week, respectively, it's important to note that women typically start with lower wages.36 As a result, the wages they are denied make up a more substantial portion of their overall income.

6. Concerns of Minimum Wage Increase

6.1 Summary of Concerns

Most critics of raising the minimum wage do not contend that paying workers more in a vacuum is a dangerous thing, but that forcing the economy and the businesses that employ these workers to an artificial degree can cause negative side effects. These include incentivizing automation, raising inflation, harming small businesses, or otherwise causing layoffs and unemployment. These arguments are more likely to be true with an immediate increase in the minimum wage to $15 an hour but have a much lower probability of happening if the increase is gradual. This section of this report will be dedicated to explaining why these consequences are unlikely to occur, and if they did occur, are relatively trivial and unimportant in determining the efficacy of a minimum wage increase.

6.2 Automation

The thesis of this opposition argument is that by making human labor more costly, businesses will opt to invest in automation more which will lead to mass job loss. However, there are three major issues with this conclusion.

- If it is true that a higher minimum wage is such a large financial burden on businesses, it is unlikely they would have the extra cash to invest in such technology unless they can immediately afford to automate a large portion of the below $15 an hour workers they employ.

- The incentive for workers to be automated exists either way. Robots do not have to pay taxes and they are usually cheaper than workers regardless of if the minimum wage is increased or not. Just because workers get more expensive does not mean robots are much more desirable for companies to invest in. Many jobs that have the potential to be automated will eventually be automated regardless of what the minimum wage is.

- Even if mass amounts of automation did occur, this is not necessarily negative. Automation is expected to create 58 million more jobs than it will destroy.37 This is because more automation allows businesses to grow quicker and employ more workers and expands the robot industry to require more employees. Just because there is a risk of automation occurring does not mean workers do not deserve to be paid more.

6.3 Inflation

Few critics argue that a raise in the minimum wage would result in the dollar being less valuable, causing inflation, but it’s still a common misconception. This is likely the weakest argument against a higher minimum wage as it ignores basic concepts of economics in three ways.

- The primary cause of inflation is when money is artificially pumped into the economy, not when wealth is simply restructured. In reality, wage increases have extremely marginal and temporary impacts on inflation. Statistical analysis even shows that gradually raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour could only boost inflation by about 0.1% per year for five years, then fade to near zero.38 For perspective, inflation over the past two years has been 100 times higher than that.

- If it were true that unemployment would increase in any capacity, this would decrease inflation because discretionary spending capacity is lower, thus there is less demand for products.

- Even in the worst-case scenario where there is a noticeable amount of inflation a higher minimum wage ensures that Americans can afford this inflation. Inflation will happen regardless of how high the minimum wage is, if anything, fast inflation is why raising the minimum wage is so necessary. Moreover, this argument insinuates that decreases in poverty are a bad thing – which is inherently fallacious because it fails to consider the entire picture of consequences.

Clearly, inflation is a cop-out argument to address the issue of low pay, making a higher minimum wage rather convincing.

6.4 Business Strain & Unemployment

By far the best ground that those in opposition to a higher minimum wage have is the risk of strain on businesses. The vast majority of arguments against such an increase are dependent on businesses losing money as a result of higher labor costs, causing them to react in some way, including but not limited to laying off employees, raising prices, automating workers, cutting hours, and even closure. The analysis remaining in this section will be dedicated to explaining why a higher minimum wage does not result in higher strain on businesses and thus does not result in the consequences. There are nine ways that the risk a minimum wage increase poses to businesses is untrue, offset, or otherwise unimportant.

- When workers are paid a higher minimum wage, they have more money to spend elsewhere in the economy. This means that businesses will receive more profit because their customers have the purchasing power to afford to purchase more goods in services. The purchasing power of low-income workers peaked back in 1968, but a $15 federal minimum wage would make low-income workers' purchasing power 27.9% higher than that peak.39

- When workers are paid more, they are more productive in the workplace which can partially offset the higher cost of labor that they demand with a higher minimum wage. Essentially, underpaid workers have financial stress, skip meals to save money, and have poor healthcare. This eventually harms businesses as well because their workers perform worse when dealing with these personal issues. Paying workers more would not only ameliorate this issue but also make them more enthusiastic about going to work and performing well.40

- A higher minimum wage reduces worker turnover by decreasing the incentive for workers to leave the job force or seek higher wages elsewhere. In the status quo, many low-wage workers jump from job to job to see higher wages, or in some instances even leave the workforce entirely because the work is not worth the low pay. This, in turn, harms businesses because they lack workers which requires costs to be spent on hiring advertisement and training new workers. A higher minimum wage would decrease the incentive for workers to quit since they will likely be more comfortable with their wages, reducing turnover rates by almost half.41

- Layoffs and cutting of hours are extremely unlikely to happen, even if the minimum wage were to be increased because the current labor shortage leaves businesses unable to afford fewer employees. 60% of small businesses are experiencing a labor shortage and 80% of those businesses have seen profit declines due to the labor shortage.42 A higher minimum wage may incentivize workers to reenter the workforce, minimizing the current labor shortage.

- A large portion of the potential job loss that could happen as a result of a higher minimum wage is voluntary. In the status quo, 13 million Americans work more than one job in order to afford the necessities to live since the wages for a single job sometimes are not high enough.43 When wages are raised, many of these workers can quit their extra jobs. This does two critical things. First, when workers no longer have to work two jobs, they can be more productive and focused on one job, which is beneficial to the business (as per the productivity response). Second, when jobs are voluntarily being left, there is a job open for someone else, making the impact of job loss much less significant. As a result of this concept, the economic reports that predict the amount of job loss from a higher minimum wage exaggerate their numbers by 1,000%.44

- If no piece of analysis is salient on its own, past precedent simply dictates that a higher minimum wage will not result in significant job loss, unemployment, or other negative consequences. Researcher John Schmitt of the Center for Economic and Policy Research studied hundreds of minimum wage increases over 13 years at the local and state level. Schmitt found that the wage increases did not show any discrete or significant correlation to job loss or unemployment.45 A higher minimum wage doesn’t just not hurt businesses, it has also historically helped them. Small businesses in states with a higher minimum wage grow almost twice as fast as in states with a $7.25 minimum wage.46

- Even if businesses are harmed in the short term, the benefits of paying workers more and preventing poverty will last far longer than any potential layoffs. In the absolute worst case where hundreds of thousands of workers are laid off, the number of possible people who could lose their job would be cut in half by the year 2025.47

- Most articles and reports that are used by advocates against a raise in the minimum wage still concede that on the net, there is less poverty. For example, a Congressional Budget Office report from February 2021 that is most commonly used in minimum wage discourse, finds that as many as 900,000 people could be left unemployed by a $15 federal minimum wage. But the report itself even finds that on net, 1.3 million Americans would still be lifted out of poverty.48 Even if some workers are left unemployed, poverty reduction is far greater.

- Layoffs are not nearly as severe of a consequence as often characterized. Simply put, it is easier to find another job with a similar wage than it is to find a job that pays higher wages. Even if someone loses their job, they are not permanently put into poverty as they can still find another job. This is particularly relevant considering the labor shortage facing America resulting in many firms looking to employ more workers. Even if some people end up unemployed, they are still able to find another job, except now, that job is higher paying.

It is true and reasonable to believe that a higher minimum wage could lead to job loss, but it’s necessary to conduct a comparative analysis to determine the relative importance of the said risk of job loss. This briefing concludes that this risk is not nearly significant enough to outweigh the benefit of higher wages.

7. Recommendations and Solutions

7.1 Summary

The working class in America experiences incredibly low wages, both in context to their counterparts in history as well as businesses' capacity to pay them. A raise in wages would result in less poverty considering that affording necessities like food and shelter, which is often inaccessible to low-income Americans, becomes much easier. However, there is indeed a risk that an abrupt increase in the minimum wage could harm businesses, resulting in unemployment. An incremental increase in the federal minimum wage is the optimal balance between ensuring workers are compensated fairly and that businesses aren’t harmed to the point of no return.

7.2 Phase-In Increase of Federal Minimum Wage

The phase-in increase of the federal minimum wage refers to a gradual and incremental adjustment of the minimum wage mandated by the federal government. Policy makers choose to implement the increase of the minimum wage over-time due to the easier adjustment to the economy.

The reason for why Phase-In increases are such a preferred method is because it allows economies to adapt to the higher wage level.49 A sudden and significant increase in the minimum wage can disrupt the labor market and business operations. By phasing in the increase over time, both employers and employees have more time to adjust to the new wage levels, reducing potential economic shocks.

Businesses, especially smaller ones, need time to plan and budget for increased labor costs. Phasing in the minimum wage increase provides employers with a clearer timeline to adjust their budgets and pricing strategies. By slowly increasing the wage, it allows for business to properly adjust for changes and can lead to millions being benefited from the small increase and boost economic productivity as a whole. This is due to the fact that companies won’t be forced to lay people off and can slowly be pushed up.50

Critics of minimum wage increases argue that abrupt hikes can lead to job losses, particularly among small businesses or in industries with thin profit margins. Phasing in the increase can help businesses adapt and potentially mitigate job losses.51

7.3 Regional Minimum Wages

In the plans for 2023, 27 increases between states and the nation’s capital will provide for higher regional minimum wages, and overall, 30 states contain minimum wages that are above the federal standard.52 While states like Washington remain the highest, Wyoming and Georgia keep scraping the bottom of the barrel when it comes to minimum wages. Although not every state has hopped on board, progress continues to be made region by region.

Over the summer alone, CT, NV, OR, and DC boosted pay for 765,000 workers with a total gain of over $615 million in wages.53 It is clear that despite the gradual tendencies of minimum wage increases, the trend has passed through countless states and regions as it improves lives and conditions for rural and urban dwellers alike.

7.4 Addressing Opposition to Minimum Wage Solutions

Opponents of minimum wage increases often contend that such policies can disrupt labor market efficiency. They argue that artificially raising wages may discourage employers from hiring, leading to higher unemployment rates, particularly among low-skilled workers. According to a survey conducted by Billshrink, lower labor costs constituted one of the top ten reasons why American enterprises outsourced their workforce to other nations.54 Consequently, an increase in the minimum wage could potentially dissuade American businesses from retaining their operations within the country, compelling them to relocate their factories to regions like China or other locales with more cost-effective labor pools. This perspective draws upon neoclassical economic theory, which emphasizes the importance of market forces in determining wage rates. However, proponents argue that the potential negative effects on employment are often overstated, as empirical research suggests that moderate minimum wage increases have had minimal adverse impacts on employment levels. In fact, studies by leading economists, including Nobel laureate George Akerlof of Georgetown University, found that employee morale and work ethic increase when employees believe they are paid a fair wage.55

Skeptics of minimum wage hikes often raise concerns about inflation. They argue that raising wages artificially can lead to price increases across the board, diminishing the real purchasing power of consumers and potentially exacerbating income inequality. However, as stated above, moderate wage increases can be carefully calibrated to local economic conditions, curbing the risk of substantial inflationary consequences. Additionally, proponents argue that the benefits of reducing income inequality and poverty outweigh the potential for mild inflation, and that other fiscal and monetary policy tools can be used to manage inflationary pressures.56

The debate over minimum wage solutions is a complex and nuanced one, encompassing diverse economic, social, and political dimensions. An intellectual exploration of the opposition to these policies reveals legitimate concerns about labor market efficiency, small business viability, inflation, and regional disparities. However, many experts argue these concerns can be addressed through careful policy design and nuanced regional adjustments.

8. Conclusion

Governments, as the primary agent of change for minimum wages, have the capacity to push for higher minimum wages to counteract pressing problems ranging from mental health, workforce productivity, exploitative workplace practices, lower purchasing power, and so on.

Expanding on the trends of increased minimum wages on the state level, we suggest the following:

- Incremental increases of the federal minimum wage to $15/hr across all U.S. states; and

- Increased discourse between government officials, economists, businesses, labor unions, and workers to optimize for the needs of all stakeholders involved

Ultimately, the potential for higher quality of life, improved financial standing, and increased worker protections make the concept of increased minimum wages a necessity. The pronounced economic struggle derived from failures in fiscal and monetary policy necessitate decisive action to mend the frayed fabric of the American labor system.

1. A. L. A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935)

2. National League of Cities v. Usery, 426 U.S. 833 (1976)

3. Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority, 469 U.S. 528 (1985)

4. History of changes to the minimum wage law. DOL. (2021, December 26). https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/history

5. History of federal minimum wage rates under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938 - 2009. DOL. (n.d.-b). https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/history/chart

6. DeSilver, D. (2021, May 20). The U.S. differs from most other countries in how it sets its minimum wage. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/05/20/the-u-s-differs-from-most-other-countries-in-how-it-sets-its-minimum-wage/

7. Flynn, J. (2023, July 4). 20+ crucial minimum wage statistics [2023]. Zippia. https://www.zippia.com/advice/minimum-wage-statistics/

9. Bradley, D. H., & Overbay, A. R. (2023, March). State Minimum Wages: An Overview. Congressional Research Service reports. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43792.pdf

10. Brady, D., & Volden, C. (n.d.). Revolving Gridlock: Politics and Policy from Carter to Clinton (Chapter 2: Theoretical Foundations). Stanford Department of Political Science. https://web.stanford.edu/class/polisci179/Gridlock2.htm

11. Weinraub, B. (1989, June 14). Bush rejects rise in minimum wage to $4.55 an hour. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/14/us/bush-rejects-rise-in-minimum-wage-to-4.55-an-hour.html

12. Kamper, D., & Hickey, S. M. (2022, September 6). Tying minimum-wage increases to inflation, as 13 states do, will lift up low-wage workers and their families across the country. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/tying-minimum-wage-increases-to-inflation-as-12-states-do-will-lift-up-low-wage-workers-and-their-families-across-the-country/

13. Dorn, A. (2022, December 16). Inflation will trigger minimum wage hikes in these states. NewsNation. https://www.newsnationnow.com/business/your-money/minimum-wage-goes-up-based-on-inflation-in-these-states/

14. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Consumer Price Index (CPI) Home. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

15. State minimum wage laws. U.S. Department of Labor. (2023, July 1). https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/state

16. Gülal, Filiz; Ayaita, Adam (2018) : The impact of minimum wages on wellbeing: Evidence from a quasi-experiment in Germany, SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel

Data Research, No. 969, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin

17. John Kaufman, "Effects of increased minimum wages by unemployment rate on suicide in the USA," Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, January 7, 2020, [Page #], accessed August 16, 2023, https://jech.bmj.com/content/74/3/219.info.

18. Michael Saltsman, "Who Really Employs Minimum Wage Workers?," The Wall Street Journal, last modified October 2013, accessed August 16, 2023, https://epionline.org/oped/who-really-employs-minimum-wage-workers/.

19. Matthew Castillon, "70% of workers are likely to quit at current $7.25 federal minimum wage in 'brutal' turnover cycle," CNBC, last modified September 25, 2019, accessed August 19, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/25/70percent-of-workers-are-likely-to-quit-at-current-federal-minimum-wage.html.

20. Castillon, "70% of workers," CNBC.

21. Tony Dokoupil, "Walmart still isn't paying workers enough, says one author calling for a $20 national minimum wage," CBS News, last modified January 17, 2023, accessed August 19, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/walmart-minimum-wage-20-an-hour-still-broke-rick-wartzman-author/.

22. Louise Matsakis, "Why Amazon Really Raised Its Minimum Wage to $15," Wired, last modified October 2, 2018, accessed August 19, 2023, https://www.wired.com/story/why-amazon-really-raised-minimum-wage/.

23. David Card and Alan B. Krueger, "Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania: Reply," The American Economic Review 90, no. 5 (2000): [Page #], http://www.jstor.org/stable/2677856.

24. Maldonado, C. (2021, June 29). Price of college is increasing almost 8 times faster than wages. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/camilomaldonado/2018/07/24/price-of-college-increasing-almost-8-times-faster-than-wages/?sh=7a27066966c1

25. Tung, I., Sonn, P. K., & Lathrop, Y. (2015, November 5). The Growing Movement for $15. National Employment Law Project. https://www.nelp.org/publication/growing-movement-15/

26. Hammond, S. (2021, July 18). Minimum wage workers can’t afford a two-bedroom rental anywhere in the country, new report says. https://www.whsv.com. https://www.whsv.com/2021/07/18/minimum-wage-workers-cant-afford-two-bedroom-rental-anywhere-country-new-report-says/

27. Galea, S. (2011, July 5). How many U.S. deaths are caused by poverty, lack of education, and other social factors?. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/how-many-us-deaths-are-caused-poverty-lack-education-and-other-social-factors

28. Tsao, T.-Y., Konty, K. J., Van Wye, G., Barbot, O., Hadler, J. L., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2016). Estimating potential reductions in premature mortality in New York City from raising the minimum wage to $15. American Journal of Public Health, 106(6), 1036–1041. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2016.303188

29. Erika Deserranno, "What Happens to Worker Productivity after a Minimum Wage Increase?," Kellogg Insight, 12-1-2022, https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/worker-productivity-minimum-wage-increase

30. Deserranno, “What Happens to Worker Productivity after a Minimum Wage Increase?,” Kellogg Insight

31. Decio Coviello; Erika Deserranno; and Nicola Persico, "Minimum Wage and Individual Worker Productivity: Evidence from a Large US Retailer," Journal of Political Economy, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/720397

32. Covielo et. al., "Minimum Wage and Individual Worker Productivity: Evidence from a Large US Retailer," Journal of Political Economy

33. David Cooper and Teresa Kroeger, "Employers steal billions from workers' paychecks each year," Economic Policy Institute, last modified May 10, 2017, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www. epi.org/publication/employers-steal-billions-from-workers-paychecks-each-year/#epi-toc-17.

34. Cooper and Kroeger, "Employers steal," Economic Policy Institute.

35. Cooper and Kroeger, "Employers steal," Economic Policy Institute.

36. Cooper and Kroeger, "Employers steal," Economic Policy Institute.

37. Vilbert, J. (2019, September 10). Technology Creates More Jobs Than It Destroys. FEE Freeman Article. https://fee.org/articles/technology-creates-more-jobs-than-it-destroys/

38. Bivens, J. (2022, September 22). Inflation, minimum wages, and profits: Protecting low-wage workers from inflation means raising the minimum wage. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/inflation-minimum-wages-and-profits-protecting-low-wage-workers-from-inflation-means-raising-the-minimum-wage/

39. Cooper, D. (2019, February 5). Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2024 would lift pay for nearly 40 million workers. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/raising-the-federal-minimum-wage-to-15-by-2024-would-lift-pay-for-nearly-40-million-workers/

40. Jayachandran, S. (2020, June 18). How a raise for workers can be a win for everybody. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/18/business/coronavirus-minimum-wage-increase.html

41. Castillon, M. (2019, September 25). 70% of workers are likely to quit at current $7.25 federal minimum wage in “brutal” turnover cycle. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/25/70percent-of-workers-are-likely-to-quit-at-current-federal-minimum-wage.html

42. Dunkelberg, W. (2021, July 26). Small business labor shortage. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamdunkelberg/2021/07/26/small-business-labor-shortage/?sh=48a8f02c1fb0

43. Beckhusen, J. (2019, June 18). About 13M U.S. Workers Have More Than One Job. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/06/about-thirteen-million-united-states-workers-have-more-than-one-job.html

44. Cooper, D., Mishel, L., Zipperer, B. (2018, April 18). Bold increases in the minimum wage should be evaluated for the benefits of raising low-wage workers’ total earnings: Critics who cite claims of job loss are using a distorted frame. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/bold-increases-in-the-minimum-wage-should-be-evaluated-for-the-benefits-of-raising-low-wage-workers-total-earnings-critics-who-cite-claims-of-job-loss-are-using-a-distorted-frame/

45. Schmitt, J. (2013, February). Why does the minimum wage have no discernible effect on employment?. Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2013-02.pdf

46. Bernstein , J. (2004, April 30). Minimum wage and its effects on small business. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/webfeatures_viewpoints_raising_minimum_wage_2004/?phpMyAdmin=Sq5GdLH0p718JY0Okckj%2CseVKud#4

47. The budgetary effects of the Raise the Wage Act of 2021. Congressional Budget Office. (2021, February). https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-02/56975-Minimum-Wage.pdf

48. Congressional Budget Office

49. Bernstein, Jared. “Gradual Phase-in Helps Employers Adapt to Minimum Wage Hike.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 30 Apr. 2014, www.cbpp.org/blog/gradual-phase-in-helps-employers-adapt-to-minimum-wage-hike#:~:text=Gradual%20Phase%2DIn%20Helps%20Employers%20Adapt%20to%20Minimum%20Wage%20Hike,-April%2030%2C%202014&text=While%20there’s%20no%20question%20that,to%20the%20higher%20wage%20level.

50. Cooper, David. “Raising the Federal Minimum Wage to $10.10 Would Lift Wages for Millions and Provide a Modest Economic Boost.” Economic Policy Institute, 19 Dec. 2013, www.epi.org/publication/raising-federal-minimum-wage-to-1010/.

51. Caplan, Bryan, et al. “Phase-in: A Demagogic Theory of the Minimum Wage.” Econlib, 5 Apr. 2018, www.econlib.org/archives/2013/12/phase_in_a_psyc.html

52. 7-1-2023, "Minimum wage increases in 2023," Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Minimum_wage_increases_in_2023

53. Sebastian Martinez Hickey, 6-30-2023, "Nineteen states and localities will increase their minimum wages this summer," Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/blog/eighteen-states-and-localities-will-increase-their-minimum-wages-this-summer/

54. James McAffrey, "Everyone Fights on $15: Evaluating an Increase in the Minimum Wage," Harvard Political Review, last modified December 10, 2022, accessed October 9, 2023, https://harvardpolitics.com/everyone-fights-on-15-evaluating-an-increase-in-the-minimum-wage/.

55. McAffrey, "Everyone Fights," Harvard Political Review.

56. "Exploring the Effects of a $15 an Hour Federal Minimum Wage on Poverty, Earnings, and Net Family Resources," Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, last modified August 1, 2022, accessed October 9, 2023, https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2022/08/exploring-the-effects-of-a-15-an-hour-federal-minimum-wage-on-poverty-earnings-and-net-family-resources.html#:~:text=Researchers%20determine%20that%20regardless%20of,families%20who%20need%20it%20most.